I’m enrolled in a certification course where I need to develop a product landing webpage. I’ve decided to have fountain pens be my faux product.

Here’s a logo image I like.

I’m enrolled in a certification course where I need to develop a product landing webpage. I’ve decided to have fountain pens be my faux product.

Here’s a logo image I like.

Found this photo I like of the young Carl Rogers…

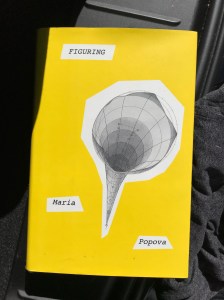

As a former aspiring astronomer, former sub-mathematics student, and ex-pseudo-poet, I might be the target niche audience for this book, so sunny & erudite & yellow like a delicious title from the iconic Springer-Verlag library. But actually this book was written for everyone, everyone and anyone that is, who has ever felt the thrillingly romantic, 19th-century or fin-de-siecle “vibrations of the soul” in the presence of celestial or aesthetic beauty, or in companionship with a kindred human spirit.

I first learned of the existence of the writer Maria Popova in a Zoom chat window in the midst of the pandemic shutdown. I had enrolled in an online course on emotional intelligence taught by a CBT therapist/writer, and during a large group session on managing one’s feelings around destructive negative self-talk I contributed a reference to Dostoevsky, to the dysfunctional yet irresistably attractive Dostoevskian universe of monomaniacal monologues & obsessions, how hard it is to let go or even set aside such psychological orientations when they have become so intertwined with one’s intrinsic identity as an artist & thinker. In response to this contribution a classmate private-messaged me in the chat expressing validation & resonance: she too felt this deep emotional, psychological, intellectual affinity with the Dostoevskian universe even though she recognized it too as a source of her suffering, a suffering that she was still loath to shed lest she should discover, in the absence of the pain & suffering in her heart, an even more dreadful & devastating emptiness. I realized that this classmate was the same person who had taken to posting poems by Rumi and others in the collaborative online community space attached to the course. She had enrolled in the course as part of her healing from the traumatic break-up of a significant relationship, a relationship, I was given to understand, that had also produced a child. All of this she revealed to me in a few words, in the hasty, abbreviated dialect of instant messaging and sudden confessional intimacy between strangers before they withdraw again into their respective corners of brooding introversion. And into this chiaroscuro darkness she also tossed a few splashes of light: one of these was a link to Popova’s website, then known as Brain Pickings, now The Marginalian.

The site is like a one-woman literary salon, assiduously erudite yet solidly accessible, an often breathless expression of Liberal Humanism 2.0, rebooting the idea that art & lterature are nourishing for the soul, even in a post-postmodern world. I can see how my suffering classmate found comfort in it. Fast-forward a few years later, and I am in an amazing indie bookstore in a college town in the Pacific Northwest when I see the hardback edition of Figuring prominently displayed on a front table. I snap it up despite its hefty weight, knowing that I’ll be risking an overage fee from my airline carrier by packing it in my checked bag and having it tip the scales past the 50-pound limit.

“Figuring” is used in several senses here. There’s the mathematical, analytical sense of working out numerical figures, as in Maria Mitchell’s and Caroline Hershel’s meticulous astronomical calculations – these two female scientists serving as historic and symbolic gravitional centers for the book to revolve around. Then there’s the painterly, aesthetic sense of human figures in the foreground of a vast cosmic panorama: figuring here is the act of sketching and delineating the outlines of these mysterious characters.

Popova plays the role of biographer in a deeply associative universe of poets, artists, journalists, astronomers, mathematicians, and thought leaders, mostly of the 19th century Transcendentalist Boston brahmin set (social/intellectual circles of Hawthorne and Thoreau and Margaret Fuller) and Amherst set (the Dickinsons). One of my correspondents complains that the second sense of “figuring” is overly privileged over the first, and it is true that the book sometimes reads like a highbrow gossip mag as if written by Anne of Green Gables. The focus, for example, is more on Maria Mitchell’s romantic passions than the mental details of her scientific works.

But I’m interested in Popova’s interest in the (often epistolary) love lives of old-fashioned, ostensibly buttoned-up intellectuals, precisely because it explores queerness in a way that cuts against the trendy grain of sex-positive third-wave feminism and performative queer theory. Maybe the sex-positivity and queer-positivity of fourth-wave feminism can be exactly about this kind of recuperation of the erotic as an expansive, inclusive expression of sensual affect that encompasses physical, emotional, and intellectual attraction alike. It’s worth reconsidering how James’s The Bostonians can be seen as super hot, and what poets in long dresses can teach us about having torrid affairs of the heart with the aid of 19th century social media.

I have been noticing and appreciating the apparent spectrum of neurodiversity among my colleagues in the local coworking space.

During my interval-training-style sessions of writing the Talking Heads post, I was frequently joined (anonymously, at a silent close distance) by one such colleague who made herself comfortable on a nearby couch with a journal and pen. For a full hour, she would write steadily and intensely without ever once stopping to look up or lift her pen off the page. Me being the perennially neurotic, self-conscious, stop-and-start, struggling-with-lifelong-writer’s-block kind of writer, I felt naturally envious of this person’s ability to stay so extremely focused on the pure act of writing, inhabiting that space so fully and selflessly that she did not seem to notice at all the colleague who approached her asking to borrow a phone charger and stood for a full minute before her in dumbfounded wonder at being so blatantly ignored. Conscious rudeness or unconscious byproduct of being laser-focused on her task? I believe it was the latter, since I have actually had several minor courteous encounters with this fully absorbed notebook writer when she was in a more socially oriented mode. A few days later I saw her seated solo in a collaboration booth conducting a Zoom meeting through an audio headset. I noticed that she has a louder-than-usual speaking voice, i.e. everyone could hear her quite audibly even from across the large room through all the customary ambient noise. So maybe her inner voice is similarly loud and has the effect of drowning out all distractions when she’s engaged in deeply personal journal work.

Neurodiverse colleague #2 is a person I confess to having a hard time not staring at, because of how they are both at once totally in control and totally out of control. Or rather these modes don’t happen at the same time but cycle on and off with apparent regularity within the same person. I see the person seated for the most part quietly and peacefully in front of their laptop, occupied in the graceful clicking & swiping movements that characterize the choreography of the modern-day information worker. Then seemingly out of the blue, in response to some stimulus from the screen, they experience a full-on emotional meltdown. Their face contorts, goes red, hot tears well up in their eyes. Heaving great yet still-silent sobs, they get up from their desk and pace restlessly back and forth across the room until the feeling eventually subsides. Then they settle back in place and when next I look over they are again absorbed in mundane work at their laptop, a peaceful half smile on their face.

I remember feeling great anxiety & discomfort the first two times I witnessed this, not knowing if a major life crisis was at hand or if the person might require intervention to avoid hurting self or others. But now I know better. This high emotional distress, this meltdown, is a regular occurrence that happens several times a day; the person seems highly sensitive and easily triggered, such that I have wondered if they are involved in social work of some kind, around distressing issues & circumstances. Yet their emotion seems more akin to intense frustration (of the terrible twos variety) than sadness. Whatever it is, I have learned to admire their ability to self-regulate and self-soothe without impacting or even being noticed by other people with the exception of, it seems, me.

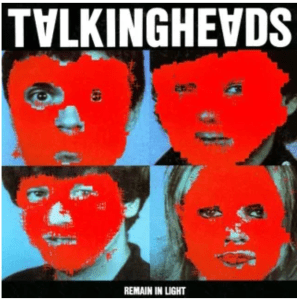

Self-isolating with a stubborn throat cold (omicron?), burning the midnight oil to meet a big quarterly deadline, striving to perfect just the right tempo & rhythm to trick beta software into behaving and not automatically deleting my hours of tedious yet necessary labor, I discovered by chance the secret to synchronizing the pace of my body & mind to the software’s arcane beat: stream this album loudly & persistently through my headphones.

That quirky, funk-heavy, Eno-mastered sound fused the anxious determination of my present to some long-forgotten moment of my pre-adolescent past, dredged up from the subconscious like some massive molten flotilla of fluorescent star material from the dark cosmic seas.

But in reality the Talking Heads had been making a steady ascent through my dumb ethos-memory over some time now, interrupting my doldrums with brilliantly timed cameo appearances. There was that frenetic machine-gun riff of “Life During Wartime,” overheard from the windows of a passing car in the parking lot of my local grocery store in the middle of 2020. In an instant, that song became my pandemic anthem, actualizing the loopy, ominous, anarchic feeling I felt when I first listened to it at age 13.

Why is it only now that I realize the iconic connection this band made between disco, post-punk, New Wave, concept art, and Parliament-Funkadelic? But perhaps this ignorance uniquely befits my singular relationship with this band, which is unlike my relationship with any other aesthetic group or movement. I knew I was meant to love this band before I ever heard a note of their music.

Actually, love is not quite the right word to describe the feeling I have. Love implies some kind of ego-regard here, a subject-object relation of admiration and pleasure. Whereas this band really represents something far more vital & essential to me, something that melts away the boundaries of the me and puts me in the midst of an object-object relation suspended over the limits of time & space.

Put in another way, the music of the Talking Heads is and was like an entire epoch and ethos that I knew I was bound to someday inhabit. Their songs were like the shape of art to come and someday, when I could finally begin to understand their music and what they were all about (cue still-image cut-in of a Chris Marker protagonist), what I would be witnessing was the moment of my own future.

As I was saying, this TH retrospective had been showing up long before my deadline-driven dance with software. There was, for example, the day-long drive to Central Oregon up the Interstate 5, with Fear of Music cued on infinite loop from my phone library. I’d never before listened to this album all the through as foreground music, and now, against a backdrop of rivers, mountains, haystacks, and fruit orchards flying by at 80 mph, I was finally hearing the genius of these songs in all their puckish, post-art-school glory.

See if you can fit it on the paper

See if you can get it on the paper

See if you can fit it on the paper

See if you can get it on the paper

Like TH, Adrian Piper is another NYC artist-intellectual of the same generation who knows a lot about funky dancing and the limits of what can be fitted and gotten on paper. A few weekends ago, I spent the final 10 minutes of an exhibition that was about to close standing alone in a taut gallery, enclosed within the dimly lit chiaroscuro of Aspects of the Liberal Dilemma, letting myself be covertly yet firmly assaulted by the confrontational soundtrack of Piper’s own recorded voice. That impeccably intelligent, educated, measured, pointed, persistent, reasonable voice — the voice of institutional reason & authority put on as a form of cultural, political drag, tugging away at the embarrassing wrinkles and loose stitches of our racial discomfort.

Sez Wikipedia: “In fluid dynamics, the drag coefficient (commonly denoted as:

My own surface area growing up was at times vacuously attenuated and ahistorically West Coast. Those East Coast avant-garde braniacs were like beings from another planet as far as I was concerned. How could I ever invent things and star-hop the way they did? How could I ever model myself after them?

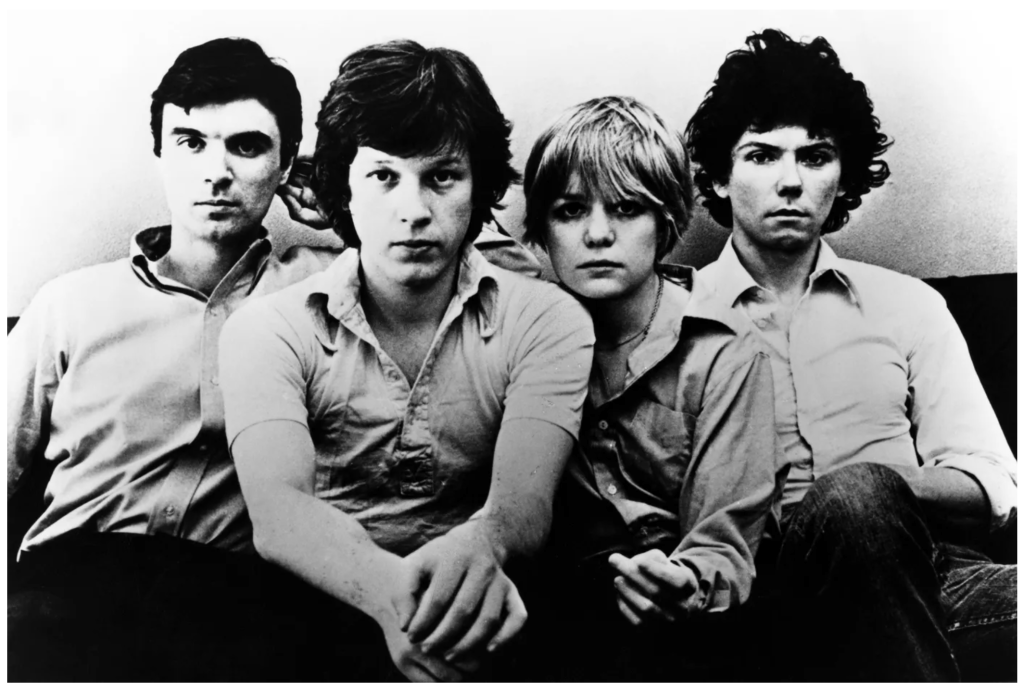

Did Piper ever meet the members of TH personally or crash one of their shows at Mudd Club or CBGB? Hard to know, yet still I place their snapshots next to one another in the ramshackle scrapbook pantheon of my mind: radical creators who nonetheless cultivated a conservative approach to personal style, the slightly nerdy, ever-so-strange art kids from next door.

These people taught me about the importance of having a killer instinct.

That live version of “Psycho Killer” prominently features Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz’s drum and bass rhythm work, which brings me to the other way that TH serves as an archetypal model: the narrative of the band’s interpersonal dynamics and eventual breakup. This is the story of the art-collective romance, the clash of personalities and ambitions, whether a band can maintain a relationship of poly-love through all its ups and downs, whether it can weather the personal changes as its members age from their 20s to their 30s and beyond.

This is the narrative which divides the band into the David Byrne camp (or for a spell the Byrne-Eno camp) and the Weymouth-Frantz camp, with Jerry Harrison dangling off to the side there as a separate free agent. Weymouth and Frantz are one of the most notable and long-lived couples in rock history, with Frantz being possibly the most devoted, supportive, and authentically feminist partner who ever existed. During TH’s trial separation in the early 1980s, Frantz and Weymouth formed Tom Tom Club, the joyously female-first, pleasure-centered project that spawned the hugely influential & oft-sampled “Genius of Love.” The song’s success reinforced Tina Weymouth’s position as David Byrne’s chief rival for star attention, and the friction is evident on Weymouth’s face as Byrne pronounces her name almost beneath his breath as the final band member at the end of Stop Making Sense.

It’s probably an oversimplification to cast Weymouth & Frantz as champions of collaborative loyalty in contrast to Byrne’s ego-based strivings, but at the same time it’s sure hard not to do exactly that. Nowadays Byrne is celebrated as an autistic-spectrum hero, and rightly so. He has successfully channeled his superpowers to do great things, even by the standards of an era populated by neurodiverse frontmen, and certainly he is largely responsible for TH’s genius lyric sensibility and tone, what my friend A once called “the post-authentic sincere.” Yet like co-conspirator Eno, Byrne has also exhibited few qualms about claiming to be the sole creator of works that were in fact collective achievements. The archetypal diva frontman running off to solo fame and recasting his collaborators as a backup band. Which calls to mind this blogger’s perennial ambivalence towards the general myth (and delusional grandeur) of the auteur.