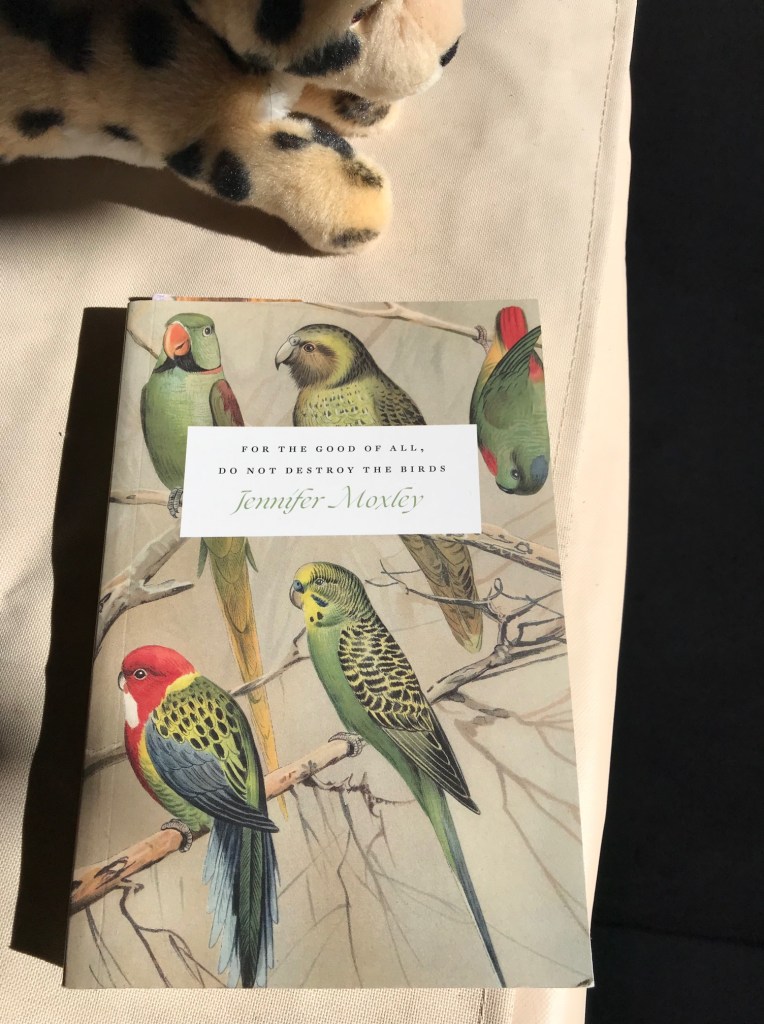

Reading this collection of bird-poetry crossed with flash-essays, I look for perches in the sunlight or on the shady, protected side of the street. Birds might alight on the back of a folding chair attached to the patio of the neighborhood cafe where I’m sitting now.

In an ecologically balanced world, birds, like poems, would be ubiquitous. You would only need to know in which direction to look (up) to find them.

In our climate-devasted world, birds, like poetry, are a collection of endangered species. They must be kept alive through intentional dedication & effort.

I’m often the first (and often the only) one in a group to notice birds in proximity. A red-tailed hawk swooping past the high-rise window when I’m sitting in a meeting with three other people. A migration of hundreds of cedar waxwings landing in staggered waves on the tallest leaf perches of my home neighborhood in the midst of the pandemic lockdown. They dominated the local airspace for about 40 minutes and were soon gone.

Moxley has that unique blend of pomo-Marxist skepticism blended with the eloquence of a classical, 19th-century-style belles-lettres. She is a writer who has always been committed to the literature of the ages, and her prose as a result is diligent, precise, and piercing, as well as exceedingly beautiful. She instructs by example, offers the patient, lifelong lesson on how to be a contemporary writer amid the seas of literary infinity.

Reading her, I feel acutely the condition of the poet, or the acute poet’s condition, as one whose solemn aspiration and obligation is to walk amongst the ages and the sages. That this solemn walk should seem strangely incongruous & out of place in the palm-lined scenescapes of Southern California where she grew up, is something I feel I can understand. I too spent an introverted childhood basking in overbaked, sunlit days south of LA. The strangeness & estrangement of being a bookish type amidst the pervasive anti-intellectualism of surf culture, of looking to my local external environment for signposts & encouragement towards my next level of personal development and finding at most the incidental, implied narrative of subdivision street-naming themes gesturing at vague arcana of categorical, encyclopedic knowledge — planets, Shakespearean characters, and styles of shipcraft in my case, the names of birds in Moxley’s case.

The poignant, uphill struggle of the poet keening to draw a connection between the tradition-rich ideas & feelings lodged in the mind and a largely synthetic, ahistoricized external environment.

Which is not to pigeonhole Moxley as a poet of flighty Romantic ideals, by any means. To the contrary, her poetics is firmly grounded in the actual, in real-life personal relationships with feathered avian beings and real-life tragedy. What is the origin story of the poet? is the question she continually asks throughout this collection. Or more precisely (to paraphrase her words), must a woman die in order for the poet to be born?

The tragic premature loss of a beloved female muse — for Orpheus, Eurydice; for Moxley, her mother — is a trauma that afflicts the poet with a singing voice of acute, nearly incomprehensible, nearly inexpressible, nearly inhuman grief. In acute grief, we become somehow irrelevant to the normative human world, or it becomes irrelevant to us. We are thrust back into the primordial emotions of our animal rear-brain, and we must don a different species of skin to match: for Gilgamesh, the skin of a lion; for the poet, the feathers & wings of a vulnerable singing creature. I think of that Greenaway film The Falls, which dances around implied avian personae triggered by a Violent Unexplained Event.

Incidentally, Moxley is one among several fine contemporary female writers who found their literary vocation in the wake of a premature maternal death. Somebody needs to write a study or something about this particular feminist phenomenon of matrilineal muse-inspiration coupled with grief.

Ultimately, this book reminds me that it’s worth it to devote our time & effort to the nourishment & preservation of a fine feathered thing — whether it be hope, a poem, a work of art, or a sand plover. We could each do far worse in our finite span of existence on this troubled, terrestrial planet as it hurtles through the skyward expanses that we wonder & dream so much about.