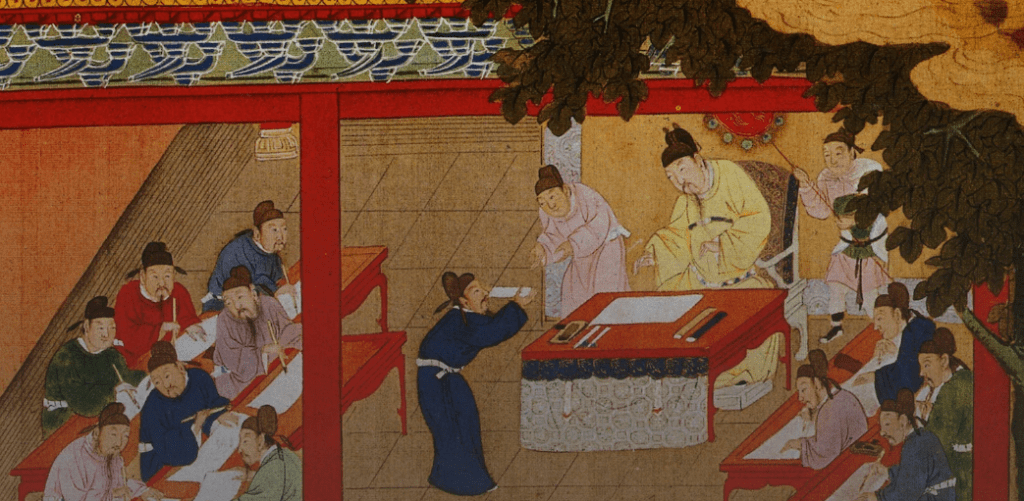

It was perhaps the most indelible institution of pre-1905 imperial China, certainly the most copied across the globe. The civil service exam system. For more than a thousand years, the proving grounds for millions of (all-male) candidates who aspired to ascend the social ladder of the world’s first and largest meritocracy.

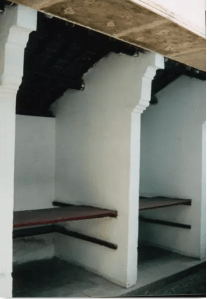

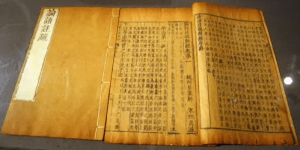

It was a merciless academic gauntlet that featured exacting penmanship as an entry-level credential, meticulous copy-book memorization of the neo-Confucian classics, and rigid adherence to an eight-part, 700-word essay format, to say nothing of the all-night candle wax, anxious journeys to the annual or triennial examination site, the three rounds of elimination from prefectural to metropolitan and finally to the palace competition, the stern pat-downs by exam-proctors-cum-police-wardens on the lookout for stashed notes and other test-taking contraband, the exam stall itself which fittingly resembled both a bureaucratic cubicle and a jail cell, the public posting of test results some 20 days post the event, glory and immediate career appointments for the top scorers, and dashed hopes for the estimated 99% of aspirants who failed to pass altogether.

I think of those exam cells in particular, mass-assembled in the courtyards of designated testing sites, outside the official buildings where robed officials officiated the event officiously. The systematic stalls exposed to the sky, with a simple wood plank serving as the desk, another plank serving as the cot, a bucket as the latrine. The written test was a marathon ordeal lasting 48-72 hours. The candidates (or victims) were expected to bring their own food. I imagine the sinking gallows feeling, the chilling gallows feeling of the test taker. Apparently some perished during the trial, since it is said the proctors followed a strict protocol of tossing the corpses of expired candidates over the wall of the test site, rather than allow family members past the barrier to collect the remains in person. It seems that some relatives near these sites during the event, anxiously cheering on their scholar-gladiators and awaiting the results. There was the feel of a high-stakes sporting event about the whole thing. What did the test-taker think, with the hopes and expectations of the entire family on their shoulders. The ultimate academic performance anxiety, in that uniquely Chinese way which pins all hopes on writing, on the page. A shared congenital neurosis perhaps, no doubt leading to situational panic attacks.

The passing rate was estimated to be a mere 1%. As such, the target of upward mobility was still quite the long shot for a peasant boy without the financial means and family connections to secure valuable study time away from the fields and private tutelage from the imperial equivalent of a Princeton Review-style test prep coach. But apparently this didn’t stop some from trying and many more from dreaming. In a populous, agrarian society of rigid customs and limited opportunity, who could blame a poor family for pushing their cleverest son toward the books? Success would mean financial security, a marked rise in social status, and escape from the toils and perils of an existence eked out through subsistence farming, subject to the chance disasters of flood and famine. An ancient tribal hunger is permanently inscribed in the casual colloquial greeting used by common folk in place of the more formal “Are you well?”: “Have you eaten yet?”

Up in the elevations of Guandong and Fujian, where crops were wrested improbably from rough slopes and rocky soil, the mountain Hakkas, poorest of the poor farmers, liked to sing the legends of students who won passage from rags to riches. For the most part these were fictional personages, folk heroes of folk ballads bellowed out in rhyming septameter or rapped in five-line stanzas to a bass-and-treble beat of handheld clappers. The bards, themselves impoverished, would go singing from door to door in the peasant villages, begging for their supper in the form of a rice bowl charitably proffered by an appreciative audience. Their narratives were bawdy and melodramatic, hardly the stuff of the literary canon, certainly a far cry from the dry Confucian classics that formed the one and only syllabus for the civil exams. The folk tales were full of feeling and entertainment, and thus unstoppable in popularity: reproduced by print houses both official and underground, read and reread and reread again, passed from hand to hand until the pages were left in tatters, they survived upheavals of migration and censorship during the Cultural Revolution, propagated with collective exuberance in all their regional variants and vernaculars.

These folk ballads are the scruffy underdogs of Chinese culture, like the character Yu who appears in the Analects. A swordsman turned unlikely devotee of Confucius, Yu is the odd man out within the master’s inner circle, a burly, emotive jock among cool, elitist intellectuals. He is depicted as a somewhat bumbling, even comical figure who endures constant belittlement from the other more polished disciples. A kind of ancient Chinese Dmitri Karamazov mercilessly hazed by a fraternity of patronizing Ivans. In the Netflix adaptation he would be played by Will Ferrell or a young Jackie Chan, had that new dragon been more befuddled than sly in bearing. His peers, as if precognizant of the millennium of canonization, ceremony, and codification to come, respond to the master’s inquiries with an economy of pith and protocol. Their prudent statements come ready-equipped with hooks for scholarly glosses and footnotes ad infinitum. I can practically see the carefully ironed creases in their mandarin robes, yet I can’t recall a single one of their names. They seem to melt and blend into a single bland, moralizing entity, prototype for the cohorts of sententious scholar-bureaucrats in the centuries to come. Yu, on the other hand, is uniquely memorable, stealing the scenes with his clumsy yet sincere flubbing. His innumerable failures and failings are relatable on the human level, as is his earnest desire to please and learn from the venerable philosopher.

The other disciples excel at reciting Confucian precepts with the proper tone of Confucian piety. Yu excels at nothing and struggles to furnish coherent answers to the moral catechisms that zing through the air like baffling verbal puzzles. What he lacks in eloquence he makes up for with the simple purity of his heart. He wants so badly to absorb the teacher’s words of wisdom, the way a child keens after the north star. When Confucius dies, Yu is the one who weeps the most effusive and genuine tears. The level of feeling he exhibits throughout the anecdotal text of the Analects goes beyond the customary devotion of disciple to master and hints at something more personal and primal.

I speculate about Yu’s origins, the psychological and sociological factors that led him from the martial arts to the philosopher’s salon. Confucius emerged during the Eastern Zhou dynasty, an era of balkanized conflict and near-constant war. There were factional states at war with one another, and rival aristocratic clans locked in internecine strife within those factions. Wikipedia tells me that there were “hundreds of wars between the periods of 535–286 BCE.” It was a time of widespread chaos, with continual shifts in leadership and ruthless expressions of ambition, aggression, and violence. To commoners, the world must have felt like a quicksand pit of elusive loyalties, lawlessness, and unsavory human nature. The poets and philosophers despaired, or turned to drink, or devised comprehensive thought-systems to curb social vice and bring order to the baggy monster of contradiction and anarchy known as feudal China. Confucianism, along with the examination system that codified its entry points, would serve as the one ring to unite all the factions under a central imperial authority. But that would have to wait until the next dynasty or so.

As a boy, did Yu see his family brutalized by rapacious grifters and bandits, his mother and sisters mishandled, his father and brothers ruined or even killed? His bearish emotionality speaks to some moment of trauma in his past. Did he turn to swordsmanship as a way of becoming a protector and defender, of wreaking vengeance upon bad fate and bad faith? Did he serve the duke of a feudal state as a member of its armed forces or was he a free agent, a swashbuckling mercenary earning his keep one murky skirmish at a time? And yet, there was something crucially missing from his life. His commanding officers were highly skilled but short-sighted, his mentors and allies consummately self-serving. His very existence must have felt arbitrary and unstable, so many careless rolls of the die leading to a tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow vacant of all hope except for the slim triumph of surviving one more day in an infernal kingdom of trickery, dishonesty, and greed.

If he’d had the spacey ingenuity to retreat from society and take to the woods, he might have followed in the Taoist steps of Chuang Tzu, another disillusioned pre-imperial dude who drafted his rugged physique to an apprenticeship of the mind. Literally known as “the robust one,” Chuang Tzu was the mercurial Brad Pitt to Lao Tzu’s steady Morgan Freeman, linked together as champions of truth and clarity in a dirty little world. Or, if I search through my Hollywood memories for other suitable archetypes, I see Chuang Tzu rambling along a riverbank with the loopy affability of an Owen Wilson, eccentric and satirical, a slippery and autonomous philosopher, ever willing to jump off the deep end of the nearest idea. Chuang Tzu was the psychedelic proto-Zen nature boy to the sage, taciturn Lao Tzu. Lao Tzu was sober and aphoristic, Chuang Tzu antic and discursive. In my fictitious Taoist academy circa 6th century BCE, students sip tea with Lao Tzu in a manicured garden, huddled around him in a reverential semicircle Confucian-style. Come sundown, these same disciples traipse like midnight ravers to a ramshackle hut out back, where they uncork wine jugs and prepare to have their minds sliced open by Chuang Tzu’s scathing wit. I like to imagine the two Taoists as odd-couple contemporaries, but it’s more likely that the old master predated Chuang Tzu by about two centuries. Chuang Tzu probably inhabited the 4th century BCE, beneath the long shadows of his famed predecessors Confucius and Lao Tzu, founders of rival schools of thought. The younger thinker made his philosophical preferences perfectly clear, and throughout his writings the precepts of Confucianism, or more accurately the disciples of Confucius, serve as the butt of his jests. Chuang Tzu counters the self-serious, pragmatic applicability of the Confucian school with his own style of meta-critical parables. Resistant to social systems and skeptical of the establishment, he offers his writings as an aid and tribute to radical individuality and freedom. He would never have wanted to see his ideas pinned down as the foundation of something so vulgar as political governance.

The swashbuckling Yu lacked both the nimble cleverness and free spirit of Chuang Tzu. He wasn’t capable of getting lost in the relativistic subjectivity of a butterfly, and he wouldn’t have seen much point in such speculations either. Ultimately Yu was more of an action than a mind guy. Life experiences had taught him that he couldn’t afford a philosophy that wasn’t firmly moored to the ground. Confucius was more than a sage and teacher to him; he was also a gentle yet firm father figure, a leader whose authority was not based on brute force, a protector who safeguarded peace not with the threat of war but with continued peace. He represented the revolutionary new way for someone like Yu, who had doubtlessly grew weary and disillusioned with paths to power that were lined with violence. If the Confucian ideals prevailed, there would be an end to war and instability, an end to the ruthlessness of lesser, unvirtuous rulers. It must have felt like a golden promise to Yu. More than a millenium later, Lu Hsun wrote of the road that doesn’t exist yet, through a land that one longs to traverse. Where the multitudes go, he wrote, there a road is eventually made. Yu wanted to be one of the makers of the most important road in his era.

The mountain singer-storytellers were scruffy like Yu the Confucian acolyte, but without the earnest high-mindedness. Many centuries and dynasties after those generous, open-door seminars offered by the sage himself, study of the Classics had become thoroughly bureaucratic and tactical, signifiers of political virtue and worldly success rather than ends in themselves. The scholars in these ballads are honest and hard-working, to be sure, hitting the books and compositions until late into the night, but their eyes are always fixed on the very specific prize of professional achievement in the form of a prestigious official appointment, and the social and pecuniary blandishments that accompany such appointments. So it comes as no surprise that the trope of the poor student who makes good on the exams also comes with a secondary trope: the revenge narrative.

In Che Long Sells Flower Lanterns, the title character is the only son of a wealthy official, the investigating censor of Yunnan surnamed Che. At age nine, Che Long has his future marriage arranged to the daughter (also nine years old) of the intendant of education surnamed Yu. Here we get a taste of the cushy old boys club that apparently characterized the society of high regional officials like Lord Che and Lord Yu. There they are in a cozy postprandial hall, toasting each other’s merits with wine and inquiring after the eligibility of their respective offspring. Lord Che’s son is a brilliant student, Lord Yu’s daughter is brilliant at embroidery, an ideal match!

Some time later, Lord Che suffers a stroke and dies, leaving his wife and young son prey to a host of con artists and opportunists. Long story short, the fatherless household is cheated out of their home and fortune and rendered destitute. Despite the misery of existence with his weeping mother in a thatched hovel, Che Long resumes his studies and finds his spirits lifted by the fraternal comraderie of his classmates, who pool their resources to give him three hundred ounces of white silver. Plot checkpoint and foreshadow moment #1: Che Long vows to repay the good-hearted generosity of his pals one day when he passes the exams.

As a young teen, Che Long resolves to take up lantern making for his first venture as the family breadwinner. He turns out to have considerable skill and ingenuity at stitching flower lanterns. The ballad declares: “On his lanterns he didn’t depict bookish wise sayings/ But he depicted famous people from earlier dynasties.” Nevertheless, he has a hard time finding buyers for his wares in the street market, and consoles himself by composing and reciting a poem on the street corner. Luckily, a young lady in a nearby mansion happens to be prepping for the Lantern Festival and orders her maid to buy some flower lanterns. The young lady is, of course, none other than Yu Jiao, Che Long’s intended bride. Following an undercover investigation, Yu Jiao deduces the true identity of the lantern seller and sidesteps the obstacles of her tyrannical father and mean sisters-in-law to stealthily slip extra bars of silver into the payment basket for her slumming, incognito husband-to-be. The money is enough to spare Che Long from having to busk lanterns any longer; from now on, he can devote all his time and energy to his studies, with the aim of one day achieving success and publicly claiming the bride who has been so clever thus far at outwitting misfortune.

When local exam season comes round, Che Long places first at the district level, then achieves top marks again at the prefectural level. For this he is awarded admittance to the prefectural school and touted as a scholar with a shining future ahead of him. In the meantime, his fairweather intended father-in-law Lord Yu is confounded by the conflicting rumors he keeps hearing about Che Long. One minute the boy is seen practically begging in the streets, next he’s reportedly crushing it in the prefectural exams. Never mind which it is, the bottom line in Yu’s mind is that he botched it on that tipsy evening in Yunnan province years ago by giving away his daughter to a pauper. He must find a way to renege on the engagement and locate a more suitable son-in-law. Someone like Zhao Long, fifteen-year-old scion of the wealthy Zhao family. When Lord Zhao makes overtures to this effect, Lord Yu jumps at the opportunity and just like that, his daughter Yu Jiao finds herself promised to two scholars, one rich, the other penniless.

Unlike many female protagonists in the mountain songs, Yu Jiao proves more than adept at hatching schemes for rebelling against her father and promoting her own aims. She arranges to have Che Long arrive at the Yu mansion bearing lavish wedding gifts, in effect announcing his intention to claim his bride. He agrees at once and with the help once again of his classmates who pool funds to purchase the gifts, shows up at the Yu compound at the appointed day and hour. Though at this point the plot looks like it’s about to converge with a scene from Gangs of New York, for Zhao Long and his entourage have also arrived with competing gifts.

But we are not in the brass-knuckled milieu of mid-Atlantic Irish immigrants but the pencil-pushing realm of imperial Chinese bureaucracy. Instead of meeting in a brawl, the rival wedding parties settle their dispute in court, escalating the case all the way to the provincial governor’s bench. The corrupt governor accepts bribes from Lord Yu and the Zhao family, and rules in favor of Zhao Long. In desperation, Che Long turns to the young master of the prominent Zeng family. Lord Zeng was, in fact, witness to the original matrimonial deal between Lords Che and Yu; Zeng also happens to be grand secretary in the court of the capital. In other words, the Zengs are the big guns here and prove to be Che Long’s saviors. The elder Zeng sends the provincial governor a threatening letter; the younger Zeng has Lord Yu dragged out from his mansion and beaten. The governor orders the case reopened so that Yu Jiao can submit to testimony and decide her own fate. In another rare moment of female agency, she declares publicly in court that she wishes to give her hand in marriage to Che Long. Thus the case is settled and the losing parties are fined (the ballad devotes lines to a description of the exact amount of each fine).

In a fit of fury and defeat, Yu disowns his daughter. Emboldened by the younger Zeng (who has the vibe of Al Pacino in The Godfather II), Che Long assembles an army of 300 to go fetch his bride by force if needed. This turns out to be a good thing indeed, as Zhao Long has hatched a similar idea. The rival gangs converge on the Yu courtyard in a riot of gongs and drums and battle it out. Che Long succeeds at liberating his bride and brings her back to his shanty shack, where they are united as man and wife in a simple ceremony with Zeng as witness.

It’s not long after exchanging vows that Che Long must leave for the capital to take part in the metropolitan exams. Once again, his school fraternity raises the neccessary funds to finance his travels and the expense of furnishing his own exam materials. Absent her newlywed husband, Yu Jiao is left to play Cinderella to her two horrid sisters-in-law, who bully and put her down to no end for her downward mobility. Yu Jiao calmly parries all their attacks with her well-aimed wit. What these mean-girl relations don’t realize is that their poor sister’s fortunes are about to turn. Yu Jiao has just discovered the secret Yu family treasure buried under a pavilion in one of the gardens pawned off to the amiable Mr. Zhang. When she uses a portion of the gold to reclaim the garden, Zhang immediately hands her the keys along with the returned interest and contract. Mrs. Che (foreshadow point #2) is moved by this gesture of good-heartedness and vows to have her son remember Mr. Zhang when he attains success. (Always these fiduciary events are noted as actions of significance, expression of true human character and relation.) Meanwhile, Che Long is proving his mettle in the examinations. As predicted, on the strength of his essay he rises up the ranks to Top-of-the-List. Here’s the passage describing the evaluation process:

The candidates were three thousand seven hundred,

From which the grand secretaries selected the talents.

From the three thousand seven hundred candidates

They selected the three hundred men of lofty talents.

From these three hundred men they made a selection:

They selected the thirty men with the highest talents.

From these thirty men they made a further selection:

They selected the three men with the highest talents.

Their essays were then placed inside a golden urn,

And the emperor lit incense and bowed to the gods,

And then took out the essay that was the best of all,

To decide which of the essays would take first place.

Wilt Lukas Idema. Passion, Poverty And Travel: Traditional Hakka Songs And Ballads. World Scientific Publishing Company.

Which is followed by a passage describing the public glory of Che Long’s achievement:

The Top-of-the-List paraded the streets for three days:

Outstanding men emerge from the students of books!

Copying the list, people spread the news everywhere;

Runners on fast horses reported the Top-of-the-List!

Changing their boats and also changing their horses

They quickly arrived at the official reception pavilion.

There lord Yu immediately asked these messengers:

“Who is the person who passed as Top-of-the-List?”

The messengers immediately answered thusly:

“Che Long passed the examinations as Top-of-the-List,

A man surnamed Chen passed as the Number Two;

A man surnamed Lin passed as the Number Three.”

“Outstanding men emerge from the students of books!” I’d like to think that such fanfare and parades were not just inventions of the oral storytellers but actual historical fact. I’d like to think that the winning essayists really were celebrated as famed major-league heroes in a ticker-tape parade, like Steph Curry and Kevin Durant cruising down a blocked-off Market Street. I’d like to think that messengers really did run through the provinces, changing horses and changing boats as fast as they possibly could to relay the names of these scholars. Did this really happen? Even if it’s narrative hyperbole, the mere fact of its appearance in folklore speaks to the paramount significance of exam rankings in the people’s imagination. Passing and even placing in the exams means everything: fame, success, wealth, power, and immortality in the verses of balladeers begging from door to door in the mountain villages of southern China and beyond.

Here is Che Long receiving congratulations from the emperor, comparable to the NBA titlests partying at the White House:

Let’s sing of the Top-of-the-List meeting his ruler.

In the fifth watch the emperor ascended the hall,

And the Top-of-the-List expressed his gratitude.

When the emperor read his statement, he smiled,

And he gifted the Top-of-the-List a gown and a cap.

He gifted him one cup of fine Dragon-Phoenix tea,

And he also treated him to a cup of imperial wine.

Each month his salary would be three thousand,

His wives were ennobled as Ladies of the first rank,

Each received three hundred ounces for cosmetics,

And all were ennobled as Ladies of the first rank.

On their head they could display crowns of gold,

They could wear dragon-phoenix brocade gowns.

The Top-of-the-List was pleased with these gifts,

But he promptly addressed the emperor once again:

“I want to pay back my benefactors with favors,

My enemies I will pay back in the same measure.”

Payback time happens with fitting force and melodrama. Che Long leaves the imperial court amid a nine-cannon salute, constructs roads, bridges, and other public works wherever he goes, and finally returns home to the Che family mansion. Like an obsequious turncoat who knows when to change colors, Lord Yu prepares many trunkloads of gifts which he plans to lavish on the homecoming scholar-official. His daughter, now the rich mistress of a prominent household, orders the courtyard gates barred to any traitor surnamed Yu and orders all presents borne by this traitor to be incinerated. Mortally shamed and chagrined, Yu slinks back to his compound and promptly expires from a stroke.

With his newly anointed superpowers, Che Long further penalizes Yu by stripping him posthumously of his lordship title. He also treats his school brothers to an extravagant banquet, recommends the good Mr. Zhang to a high court appointment, condemns Zhao Long to the perennial status of student by prohibiting him from ever attempting the exams, and has the corrupt judge and all who swindled the Che family executed by the sword. After three years, the Yu family is reduced to hocking wine in the streets to mete out a living, in mirror retribution for Che Long’s early struggles as lantern seller. Che Long eventually shows mercy by gifting his Yu brother-in-law with fertile lands because they never personally offended him and fetching Yu Jiao’s mother out from poverty because she had supported her daughter’s marriage choice from the start.

Thus the storyteller ends the tale with an appeal to its audience to “read it thoroughly to grasp its intent.”

Che Long’s tale is not the only but perhaps the best of the scholarly rags-to-riches narratives, for its steadfast melodrama, bipolar plot twists, and detailed forays into Qing Dynasty legal procedures and general bloodlust. Nevertheless, other ballads depict the student success-story with similar glory. There is the poor student Gao Wenju who earns top rank in the metropolitan examination and is rewarded (or cursed) with marriage to the daughter of an influential minister. And there is Zhao Yulin, the destitute scholar who busks his way to the imperial exams as an itinerant banjo player while his wife Liang Sizhen endures the meangirl jabs of her three rich sisters. Upon achieving Top-of-the-List, Zhao Yulin is awarded a black gauze cap, dragon gown, and jade belt, all personally presented by the emperor. He is also paraded on horseback through the streets of the capital for three days. A band of fiddles and drums, also on horseback, follow him as people stream out in mass to catch sight of the celebrated scholar.

So went the songs of the mountain peasants who dreamed of escape from their impoverished existence, of wrongs righted, of the evil & powerful brought down low and the poor & studious made mighty.