I’ve been thinking about doing something like this for a while now. There is the kind of writing that is private and kept for oneself, there is the kind of writing that is meant to be public and published, and then there is the kind of writing that is neither, that is ephemeral & evanescent, meant to pass as quickly as it’s written, or alternatively and just as abruptly, morph & grow into something more durable.

So let this be a space for the kind of writing that is neither, writing that escapes from its source of darkness and yearns for light and air, for a little breathing room to expand and see what becomes of itself.

2.

In a 1991 interview with Chuck Close, Vija Celmins talks about being in her teens and coming across an Ad Reinhardt article that prompted her to pursue the art of removal. What is left over in art after you remove all the techniques of traditional aesthetics, after you throw away texture, brushwork, calligraphy, sketching, forms, design, color, and invention? What’s left, she realizes, is:

a kind of poetic reminder of how little a work of art really is art, and how elusive it is to chase the part that excites you and turns one thing into something else.

Later when she starts to make the ocean drawings based on the seascape outside her Venice Beach studio, she concludes that her art has evolved into something even more essential:

One thing led to another. When I started looking I began to look more at my own work, and I think I made the work more about looking. Essentially, it’s very conceptual work – it’s about looking.

After years of practicing disciplined removal, Celmins’ art boils down to the plain act of looking.

3.

What is left over in writing after you remove all the conventional elements associated with “good” writing, after you throw out composition, form, style, rhetoric, ornamentation? You’re left with a pile of words on the page, the act of recording something (an event, object, thought, feeling) with language. Stripped down to essentials, writing is basically the act of recording. A record, a log.

There’s something else though. To borrow a page from Celmins again (in an interview available from the Kanopy channel), the artist has said that she wants to remove her ego entirely, remove all expressive traces of herself from her work, in a rebellion from abstract expressionism towards a more objectivist aesthetic. She has said that the only trace of the self that she wants to leave for the viewer is the simple evidence that the drawing was made by hand. The pencil strokes, the marks made on the surface of the paper: these are the only signs needed of the artist’s hand, these constitute the artist’s signature.

Typography obscures the physical imprint of the writer’s hand on the page, so there isn’t that same visual signature in writing as in drawing and painting. Instead, a writer marks the text with the personal evidence of their character, their attitude, their tone. A writer signs a piece of writing with their voice.

And in the stripped-down mode of writing that is the log, this signature is reduced to something simple and quiet and perhaps hard to detect. The signature on the log is not the writer’s voice at full public volume or even intimate conversational volume. It is their voice in perpetual modulation between existence & nonexistence, the sparest presence of this voice. It is the smallest, indivisible grain of the voice.

4.

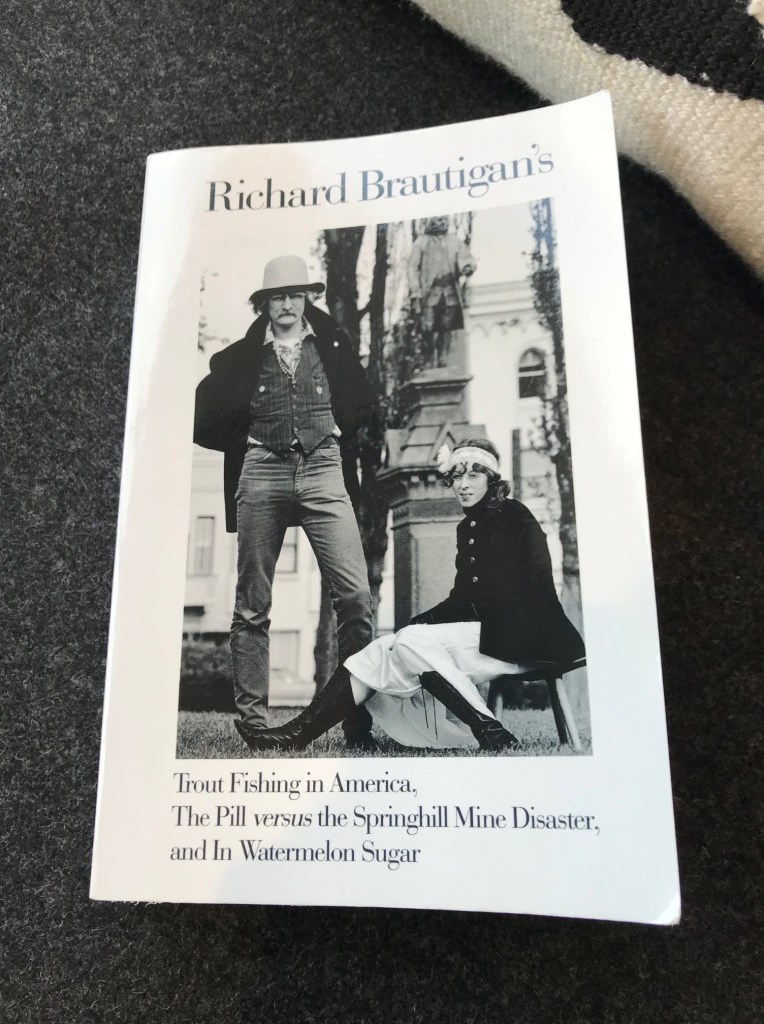

So I’ll begin by logging a few brief notes on Richard Brautigan, who I’ve been long overdue in reading. Recently I finished this triple-volume omnibus, my introduction to his writing:

A Brautigan poem is like a hinge – the kind of hinge salvaged from a battered old antique door from an even more antique, rundown house, with its krufty palimsest of rust, dents, ragged screw holes, and caked-on decades-old paint. It’s a marvel to witness the remarkable object that such a hinge can be, the way it opens and closes and opens up again, its power to pivot and bear great weight with the lightest of movements.

Trout Fishing in America is like an entire chain made up of hinges, which is to say it is held together by the interlocking logic of poetry without itself being a poem. It shows what can be done when you construct a novel not from pieces of fiction but from pieces of poetry, or a bunch of hinges and trout streams.

Roberto Bolaño would never have existed if not for Poe and Pinochet, but perhaps most of all he would never have existed if not for Brautigan. Specifically the mythic Juan García Madero sections of The Savage Detectives. For the source of García Madero’s Mexico City bookstore and Mexico City exploits, I see that I need look no further than the “Sea, Sea Rider” chapter of Trout Fishing. It is a chapter that could spawn an entire bookstore’s worth of books.

The Brautigan narrator voice of Trout Fishing and The Pill versus the Springhill Mine Disaster can be brash, hard-drinking, and macho. But the Brautigan narrator voice of In Watermelon Sugar is quiet, gentle, almost childlike. There’s a speculative wonderment and vulnerability here that makes it especially hard to read this part of his bio:

His early books became required reading for the hip generation, and Trout Fishing in America sold two million copies throughout the world. Brautigan was a god of the counterculture, a phenomenon who saw his star rise to fame and fortune, only to plummet during the next decade. Driven to drink and despair, he committed suicide in Bolinas, California, at the age of forty-nine.

It is hard to read that a writer who had so much capacity for joy, invention, and comedy also had a bottomless capacity for despair. But it so often is like this for artists, this capability to be fully, desperately present within both the extreme highs and lows of existence.

5

I write these notes now while sitting on the seventh floor of an office building near the bayshore. It’s a beautiful day and I can see the waters of the entire San Francisco Bay through windows on either side of the building. Oakland, the City, and the Bay Bridge are behind me; looking ahead, I can see the Berkeley Marina, the Richmond refinery, and the headlands of Marin rising up from the far shore.

The Bay Area is much altered since the 1960s, and many of the places and sensibilities found in Brautigan’s books are now gone. Still, you can find some traces, if you know where to look. I know for example that I can pick through a barrel of Brautigan-style hinges at the salvage/reuse yard off of Ashby Avenue, the present-day incarnation of “The Cleveland Wrecking Yard” with its used trout streams sold by the linear foot.

And word is that if you cross the bridge over to west Marin, head down the XXXXX road towards the ocean, turn XXXXX at the gas pump by the redwood grove, go winding down a few more miles past the cemetery and farmstand and then turn XXXXX again towards the sound of the running creek, you’ll wind up at a place that’s exactly like the beautiful communal iDEATH of In Watermelon Sugar.

But much of Brautigan’s Bay Area has indeed sadly vanished. The skyline dominated not by dreams of iDEATH but billboards of iPhone.

Come end of September, the desk I’m seated at now will also vanish; I and the other individuals who sit here will be forced to relocate our roving workstations to other buildings. So lately I’ve been spending more & more time here like a thirsty traveler, drinking in this magnificent view whose days are numbered for me.

I scoot all the way over to the far edge of the window to look at the Ghost Ship memorial that’s bobbing in the water and slowly swiveling around its moorage a quarter mile from the highway. The creator of this memorial is also now gone, tragically, prematurely. So I journey over to the shore with my phone and think of all the writers and artists present and past who have tried and failed and succeeded to make this Bay a home for themselves and their art, and I hold this moment silent for the ones who left us too early.